Download the PDF

Introduction

The drivers of alpha in middle market buyout companies can hold great appeal for private equity investors.

In addition to being less concentrated and more fragmented than the large-cap market, buyouts (mid-market) tend to have high growth potential, motivated management and more significant opportunities for value creation through operational efficiencies.

In contrast, large-cap buyouts, while also a compelling investment opportunity, historically have a higher correlation with overall market beta and can be more susceptible to macro economic effects (e.g. interest rates).

Each has a well-earned place in private equity (PE) portfolios. However, while diversification is important when allocating, it is not as simple as merely including both mid- and large-cap buyouts in your portfolio. Both can provide compelling returns, but these returns come from different risk drivers.

This piece explores the different risk factors that dominate large-cap and mid-market buyouts. It argues for the need to weigh an appetite for returns driven from operational and managerial risks, which are more prevalent in mid-market deals, against the returns emanating from market and financial risks more inherent in large-cap investments.

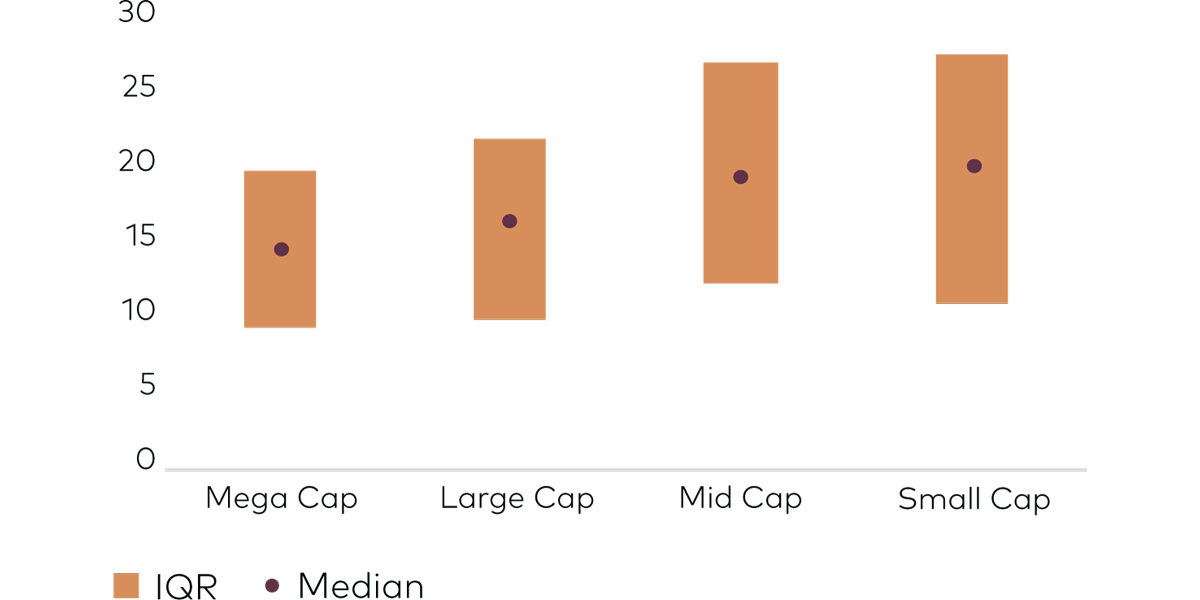

Once the decision to allocate to mid-market is made, manager selection is important. Although the mid-market sub-sector can offer higher median returns, there is more dispersion in manager performance than in large-cap managers. Investors who diligently seek out managers who can demonstrate proof of concept, strong networks and sourcing ability can potentially reap significant rewards.

The what: defining mid-market

While definitions differ, we see the sweet spot of the mid-market typically including companies with enterprise values ranging from US$100 million to US$500 million. Companies in this range are generally sufficiently mature to weather economic challenges while remaining agile, adaptable and offer significant scope for growth.

The why: the appeal of the mid-market

Profiting from mid-market investing requires understanding and managing the operational and managerial risks associated with companies progressing along the maturity curve.

We characterise these risk levers as more operationally focused than in large buyouts.

For example, companies often come with a ‘small company premium’, stemming from growth potential and a motivated, typically smaller management team focused on shoring up the company’s foundations. The potential for geographic expansion is also a possibility. These levers have the potential to result in greater revenue and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation (EBITDA) growth in smaller companies.

Additionally, mid-market buyouts can provide more exit opportunities compared to large-cap investments due to the size differential, creating more avenues for potential alpha generation. As illustrated in Figure 1, in recent exits, more than a third of deals since Q3 FY21 (3Q21) have delivered a total value multiple (TVM)1 of 3x or higher.

Figure 1: TVM distribution of realised deals by deal count (3Q21-3Q23)

Figure 1: TVM distribution of realised deals by deal count (3Q21-3Q23)

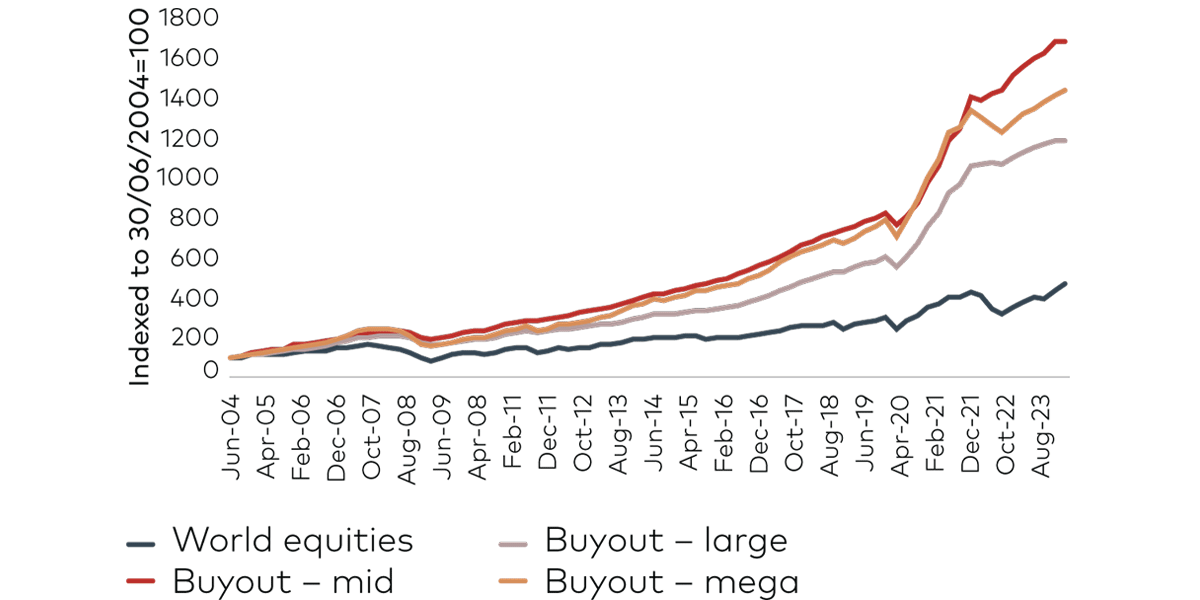

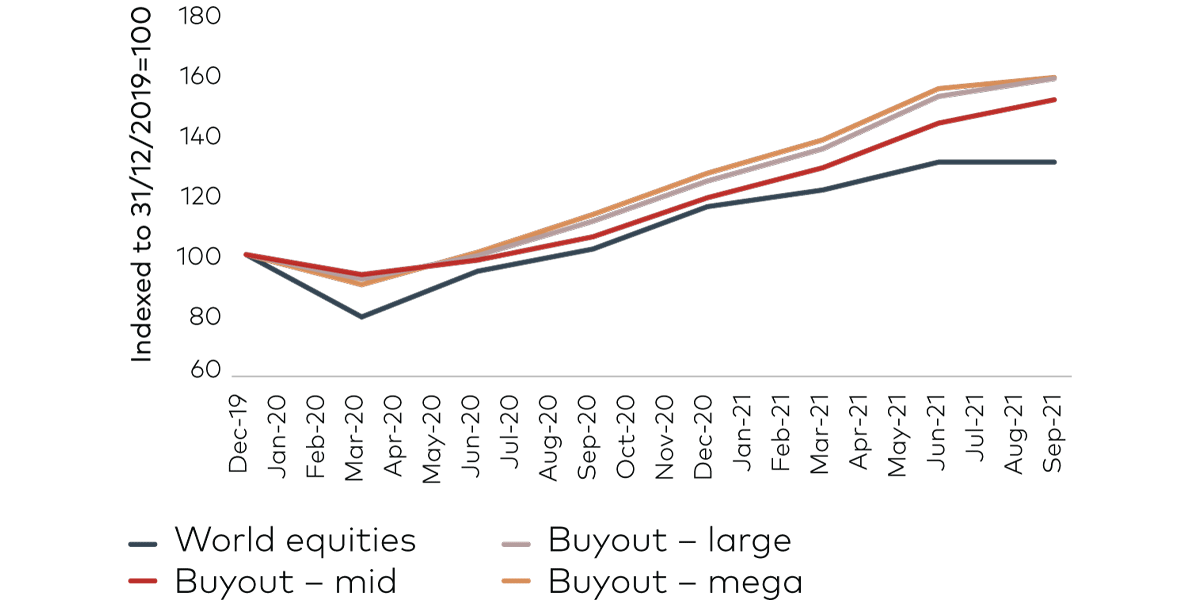

The following charts show performance of the mid-market against listed equities and larger PE buyouts over time, during periods of economic uncertainty, and in the current market. Figure 2 starts by demonstrating the outperformance of mid-market funds over a 20-year period.

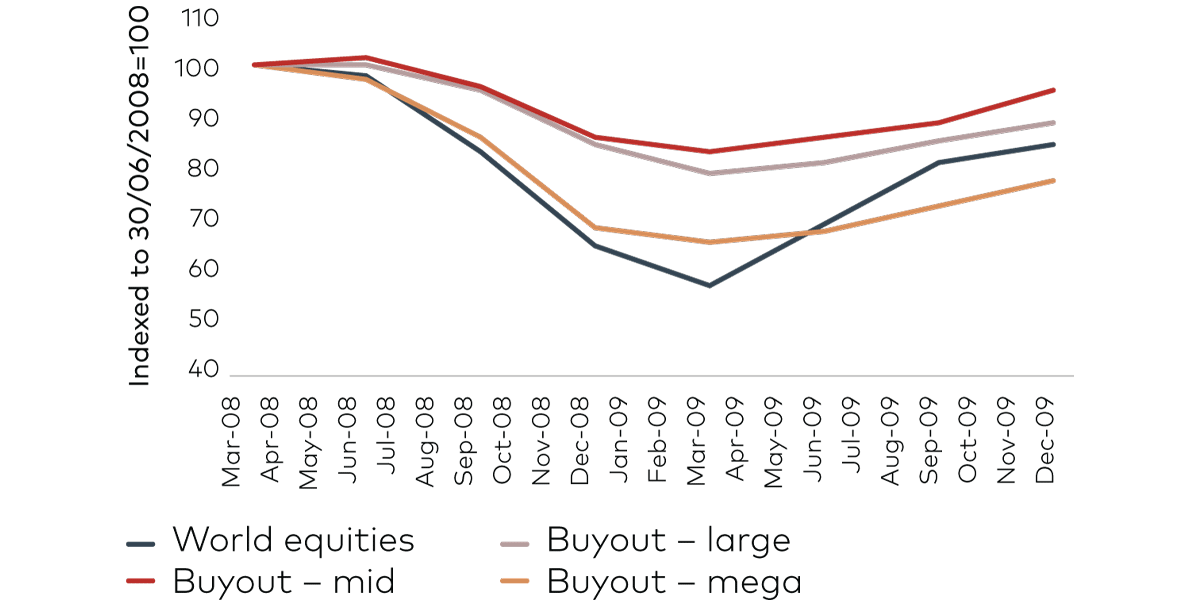

While it is evident from Figure 2 that PE buyout investments can offer significant value above listed equities, the choice between styles is more nuanced. There is certainly a home for large-cap and mega-cap buyouts, but investors need to be aware that these have greater exposure to financial and market risks, thus their performance is more correlated to general market beta. Figure 3 demonstrates this beta in the outperformance of the mid-market during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), a demonstration of its resilience to economic uncertainty.

Figure 2: Equities and mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance across time periods

Figure 2: Equities and mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance across time periods Figure 3: Equities and mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance during the GFC

Figure 3: Equities and mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance during the GFC

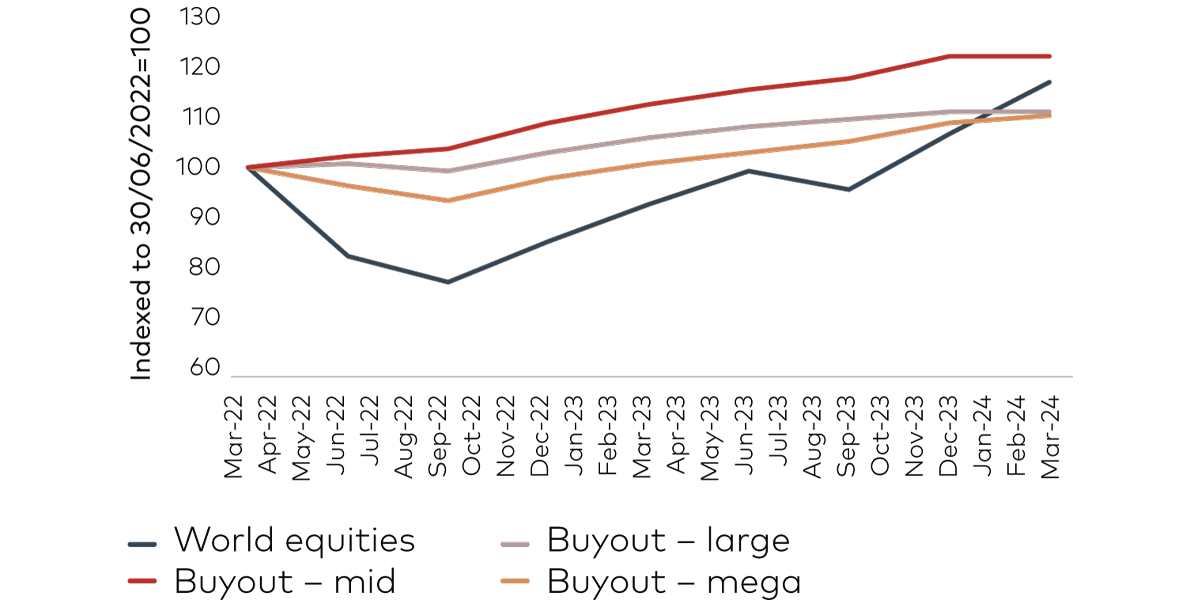

Figure 4 shows the outperformance of larger cap buyouts during COVID-19. The performance highlights the mid-market being less correlated with equities and GDP when compared to larger cap buyouts. Thus it had less of a drawdown during the market downturn and the corollary, during the period following April 2020, where public equities performed well, large- and mega-cap buyouts outperformed the mid-market.

Figure 5 shows the outperformance of the midmarket in the aftermath of COVID-19 through a period of increasing inflation and interest rates. This outperformance may be attributable to the lower leverage in mid- market companies when compared to their larger counterparts, hence more muted exposure to the rising interest rate environment.

Financial risk for large-cap buyouts primarily arises from greater leverage, with large-cap companies generally deriving more of their equity performance from debt financing. This leverage comes at the cost of greater sensitivity to the macro environment. This was particularly evident in the 2022/23 underperformance of large- and mega-cap buyouts during the period of higher inflation and interest rates, in which mid-market buyouts showed more resilience to the market conditions. From June 2022 to March 2024, mid cap saw an average (annualised) return of 10.06% compared to 5.34% for large-cap investments, as illustrated in Figure 5.

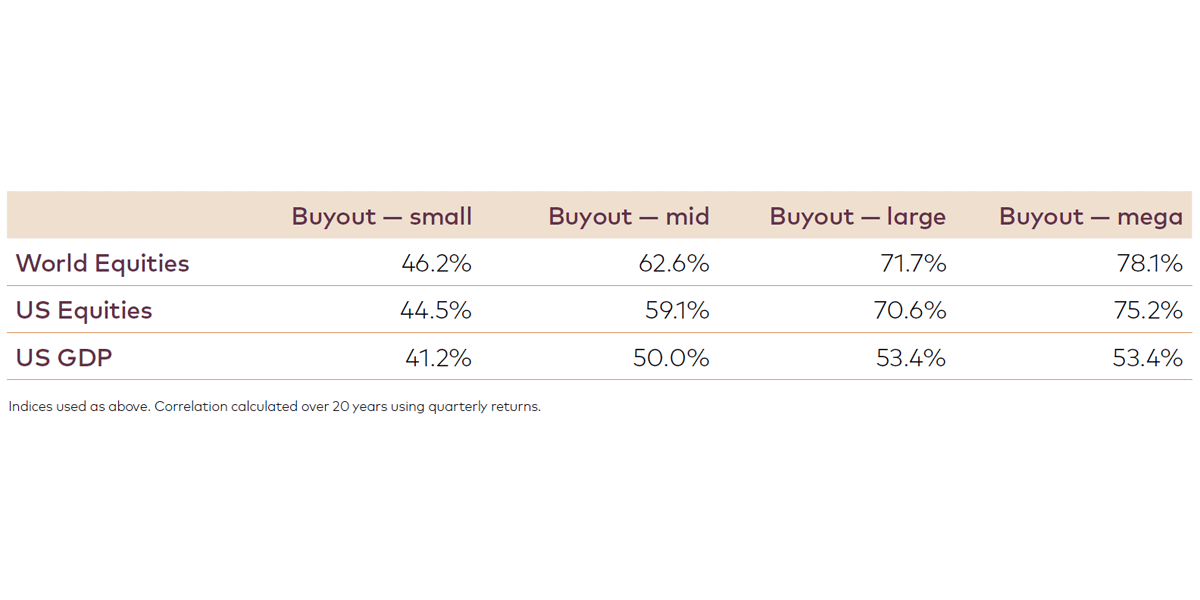

The increased leverage in large- and mega-cap buyouts, coupled with the more market-driven margin growth, often leads to a higher correlation with broader GDP and listed equity markets, compared to the small- and midmarket (see Table 1). Many investors appreciate this correlation, as it signals a great potential for return during equity market rallies. Conversely, mid-market buyouts typically underperform their larger brethren in bull markets but achieve more consistent outperformance over the long-term. This is evidenced by the mid-market realising an average return and Sharpe ratio of 16% and 1.2, versus 15.4% and 0.9 for large-cap buyout over the last 10 years.2

Herein lies the decision for investors — reap the performance aligned with market beta associated with large-cap buyouts or enjoy the more alpha-driven consistent outperformance of the mid-market? We see a place for both; however, we note those mid-market return drivers are more controllable over the long-term — especially with the right manager.

Table 1: Equities and gross domestic product (GDP) correlation matrix

Table 1: Equities and gross domestic product (GDP) correlation matrix Figure 4: Equities, mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance during COVID-19

Figure 4: Equities, mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance during COVID-19 Figure 5: Equities, mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance through a rate hiking cycle

Figure 5: Equities, mid-, large- and mega-cap buyouts performance through a rate hiking cycleThe who: choosing a mid-market manager

By definition, mid-market buyouts have moved through the risks inherent in infancy and demonstrated resilience to varied market conditions.

However, operational risks offer more opportunity for improvement when compared to their larger counterparts, so it is critical when selecting a private equity fund manager to choose managers who are sector specialists or experienced business operators. These managers can not only deliver capital inflows to the business, but also provide the advice and guidance to drive performance and growth through the execution of business plans, enhancing sales, professionalising governance and back office procedures, and streamlining procurement.

Illustrative of the need for considered fund manager selection is the net internal rate of return (IRR) dispersion shown in Figure 6. The interquartile range (IQR) shows the potential for highly favourable net IRR at the top end of the range, compared to large- and mega-cap buyouts. However, the dispersion of returns is certainly higher for mid-market, which highlights why fund manager selection is more vital. If a fund manager can establish they have the ability to add value by harnessing mid-market alpha drivers then we believe it is reasonable to expect to rule out performance in the bottom third and fourth quartiles of the IQR range.

Figure 6: PE buyouts net IRR dispersion. Source: Preqin Market Benchmarks, Small to Mega Cap Buyout, vintages 2016-2021

Figure 6: PE buyouts net IRR dispersion. Source: Preqin Market Benchmarks, Small to Mega Cap Buyout, vintages 2016-2021

When selecting a fund manager, sourcing ability and networks are also key. A manager should be looking to gain alpha through asset choice, favouring companies in a growing market with long-term tailwinds, as well as a protected position; that is, assets supported by a structural trend and with demonstrable barriers to entry.

Alignment with specialist fund managers is vital. Managers should demonstrate skills specifically suited to the types of companies being targeted.

Specialisation may be in the form of deep sector expertise, which can be additive both operationally and strategically for smaller companies that would not otherwise have access to these capabilities. A specialist mid-market manager might also look for less heavy asset intensive investments, allowing for higher margin growth and pricing power. For example, an investment in healthcare innovation is supported by the structural shift in demographics, while also having a protected position through a high barrier to entry due to the required research, technological and medical capabilities.

Specialisation could also be centered around investment style, as we see in buy-and-build strategies that are built around consolidating fragmented niches. A final consideration for investors when selecting a mid-market fund manager is alignment with company management. This is typically stronger with highly motivated, emerging managers, where there is alignment with business growth through incentives and a drive to build track record. Given they are earlier in life as a General Partner (GP), they are less able to take a “portfolio approach” to investment outcomes — they are more likely to be highly motivated to see every deal succeed.

It is important not to confuse "emerging" with "inexperienced" private equity managers. Emerging managers must still be able to demonstrate they have an experienced team but be housed in a GP that offers them more alignment on the outcome. In large cap buyouts, on the other hand, managers may have more diluted incentives than mid-market managers around deal outcomes, which has the potential to dampen the drive needed to uplift performance and realise growth potential.

The when: why we like mid-market now

Many believe equity markets are now edging into overvalued territory and rate cuts have now commenced in the US and other advanced economies.

The correlation with equity markets may send large-cap investors looking elsewhere for alpha, including to opportunities that are more resilient to the vagaries of market movements. Enter stage left, mid-market companies. While some investors will naturally seek taking on the controllable operational risks of the mid-market, even those who prefer market beta would be right to take a closer look at the mid-market in the current environment.

Citations

- TVM represents the total value of the investment (realised and unrealised) divided by total capital invested.

- Sharpe ratio calculated using annual returns and standard deviation and assuming a risk-free rate of 2.5 per cent.

- As at 30 June 2024 this represents Gross Assets under management, calculated as (i) the total market value of gross assets managed by QIC entities; (ii) undrawn commitments; (iii) excludes multi-asset derivative exposures.

Further information

QIC is an international institutional manager providing risk adjusted returns for the clients we serve. With more than ~A$119 billion3 in funds under management, we have grown into a leading Australian specialist manager in infrastructure, real estate, private debt, private equity, natural capital and liquid assets for ~115 institutional investors internationally.

QIC Limited ACN 130 539 123 (“QIC”) is a wholesale funds manager and its products and services are not directly available to, and this communication is not intended for, retail investors. For more information about QIC, our approach, clients and regulatory framework, please refer to our website www.qic.com or contact us directly. Do not copy, disseminate or use, except in accordance with the prior written consent of QIC.